The history of the firm | Since 19th century into the 21st

The Kielman family originally lived in the borderland between Germany and the Netherlands. At the beginning of the 19th century, the family settled on Polish soil. Tomas Kielman, the leader of the clan, had been appointed manager of a large estate in Szczepankowo, which fell within the Łomża Governorate. In 1880, one of his sons, the 18-year-old Jan, later known as “the first”, left the family home and traveled to Warsaw to make his fortune.

Once in the capital he began training to work in the confectionary industry, but quickly changed his mind and took a job in one of Warsaw’s many shoemaking workshops. After a three-year apprenticeship he received the title of “master” and went on to open his own workshop on the lively Chmielna Street, house number 3.

Jan was a determined and resourceful young man. Before long, he married Marianna Doley, the daughter of a wealthy family of Warsaw businessmen. He used the dowry he received to expand his workshop, which developed from a modest business into a prosperous firm. As the years went on, the shop facing the street was joined by a workshop and warehouses in the annex, where leather and finished products were stored. It was a good time for entrepreneurs, thanks to the booming economy at the turn of the century and the ready market in Russia. It sometimes happened that nearly half of the year’s production went to contractors in Saint Petersburg.

The First World War did not have a significant impact on the company’s fortune. Despite limits on production and an end to exports to Russia, nothing threatened its position in Warsaw. And despite the urgings of his father-in-law, Jan steadfastly refused to mechanize production, preferring to supervise technical matters personally. For her part, Marianna tended to the finances by ruling the shop with a firm hand. They made a point of spending their free time actively; summers were spent rowing a narrow boat on the Vistula; in the winter they traveled to the mountains.

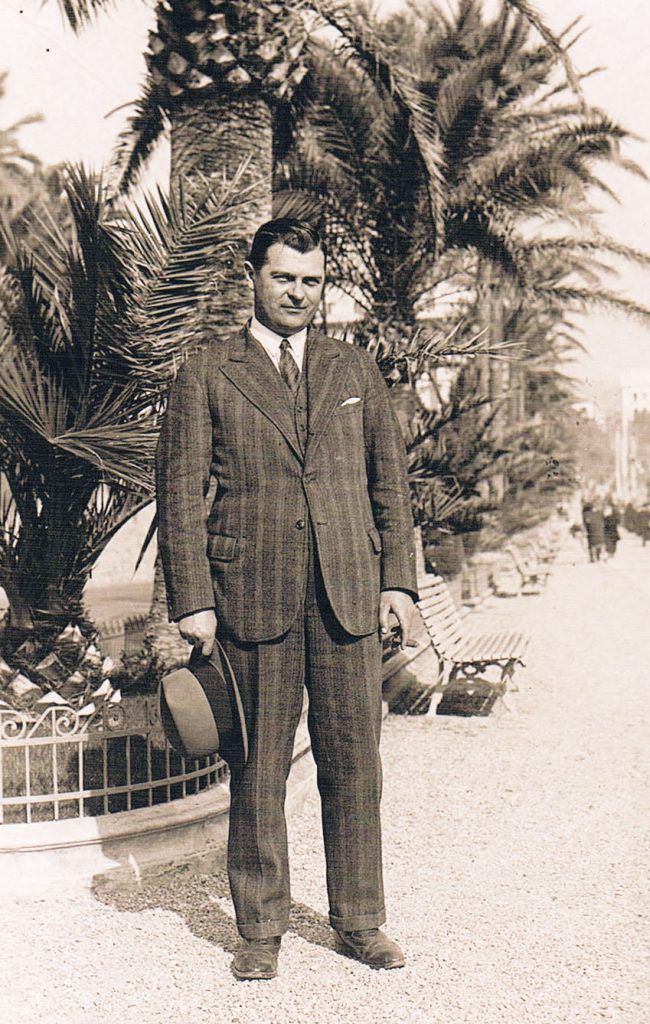

Their two children were well brought-up and carefully educated. Wacław began studying at the Lvov Polytechnic, while Julia studied philology at the University of Warsaw. Wacław’s studies were cut short by the Polish-Soviet War of 1920. After taking part in the dramatic defense of Lvov, he resolved to travel to Belgium. Later, with a diploma from the Antwerp Business Academy in hand, he obtained an internship at the already famed Bally company in Switzerland. His goal was to enter into a partnership with his father after earning the title of “master shoemaker”. Before long, he was convincing his father to install one of the first neon signs in Warsaw and to place a brass fountain with a floating shoe in the shop window to accentuate the quality of shoes made by Kielman.

In the twenty-year period between the wars, Warsaw abounded in shoemaking workshops that offered world-class services. Among the nearly four hundred shoemaking workshops, the leaders were the legendary Hiszpański workshop, past masters of men’s evening shoes and sports shoes, Leszczyński and Struś Co., which specialized in light women’s slippers, and the small Niedziński workshop, reputed to make the best riding boots.

Kielman was therefore all the more surprised when, in the spring of 1921, he received an order from a French major by the name of Charles De Gaulle, who just before ending his work on a military mission in the town Rembertów outside Warsaw, requested that a pair of officer’s boots be made for him. When this order was fulfilled with particular success, it was decided that officer-style boots and other riding boots would permanently be added to the company’s product catalog.

In 1927, the largest order in the history of the company was received. Female courtiers accompanying Amanullah Khan, King of Afghanistan, on a tour of Europe, ordered a total of two hundred pairs of slippers, claiming that they would never find better ones elsewhere. The ruler procured various goods for his own needs and those of Afghanistan in the countries he visited. From Poland he carried away a contract for locomotives and a substantial number of women’s shoes.

Other prominent customers during this period included: President Ignacy Mościcki, General Władysław Sikorski, Jan Kiepura, Adolf Dymsza, Mieczysława Ćwiklińska, Stefan Wiechecki, Wiech, Marian Brandys and a young Hanka Bielicka, who would later claim never to have worn shoes by any firm but Kielman.

In the 1930s, the shop at Chmielna 1/3 had several display windows, there were sofas and couches to sit on, and at the door stood a Swiss soldier in uniform. Two telephone lines were installed to facilitate communication with customers. Finished shoes were usually delivered to a customer’s house with a penny for “good luck” in the box.

There is no precise numerical data on the number of employees at the beginning of the 20th century, because the company’s documents burned along with the rest of the office during the Warsaw Uprising of 1944. It may be estimated, however, that well over 50 people were employed, and that this number remained constant for a long time. Of course, the most important employees were the masters and the qualified journeymen – shoemakers and craftsmen specializing in shoe uppers. The latter were about thirty in number. Each was capable of sewing between 2 and 3 pairs of shoes each week, which gives an idea of the firm’s capabilities at that time.

The Second World War was of course a very difficult time for businesses and families. Despite the fact that the occupiers allowed business to continue and Germans made up a significant percentage of the clientele, the family was moved from its luxurious apartment on Konopczyńska Street to 34 Mokotowska Street, just below the extraterritorial sixth floor guarded by the emblem of Switzerland. During the uprising that followed shortly thereafter, the shop and the workshop were completely destroyed. But as luck would have it, the contents of the warehouses did not go up in flames, but ended up in the hands of the insurgents. Wacław and his immediate family settled in the Warsaw suburb of Józefów; the rest of the family was scattered – some dying, others emigrating.

The company’s employees met with a similar fate. After the war, Wacław rebuilt the company, but it remained much smaller than its prewar incarnation. Together with his partner Leon Solnicki, he rented a small space at 6 Chmielna Street, a modernist tenement building designed by Henryk Stifelman in 1938, almost right across from the prewar address. Despite its dilapidated ground floor, the building was surrounded by houses that were in relatively good condition. Some tools, skins and lasts had been found in the ashes of the previous location, making it possible for the company to return to some extent to its prewar activities. Former employees returning to Warsaw helped immensely with this.

Unfortunately, it quickly turned out that despite the initial postwar enthusiasm the dismal times of the new system were at hand. Suddenly there were problems with the food supply – unheard of before the war – and it sometimes happened that an order could not be fulfilled unless the customer supplied their own leather. When Wacław Kielman was nominated for vice president of the Warsaw Chamber of Crafts in the 1950s, there were loud objections on the grounds that he could not serve as president for having consistently refused to join the Polish United Workers' Party or any other political party. Unlike other Warsaw shoemaking workshops, the Kielman company – as the last representative of prewar traditions – was barely tolerated by the new authorities. Each time he was summoned for questioning by state officials, Wacław would bring along a sweater and a toothbrush that he had set aside in case he got arrested. During these meetings, they gave him to understand that in the People’s Poland there would be no room for private businesses and it was only a matter of time until the firm would be shut down. To harass him more effectively and keep his company from developing, they decided without consulting him to move another craftsman – a watchmaker from the provinces – into the space that he had renovated at this own expense. Depending on the doctrine in force at a given time or the whims of a state functionary, he was only permitted to employ two or four employees in production. Auditors hunted for even the slightest irregularities in how the books were kept. Nearly every shred of leather had to be described and recorded, and any violation carried the threat of draconian fines. The result of this chicanery, coupled with the risk of tax offsets which ensured that no company had the right to rise, was that Jan II, the grandson of the founder and the son of Wacław, no longer staked his future on the shoemaker’s trade; after graduating from the University of Warsaw, he became a lawyer. At the same time, he developed his lifelong passions: sailing and rowing, mainly as a member of the Warsaw Rowing Society, the oldest sports club in Poland, founded in 1878.

The 1970s saw unexpected improvements that made life more bearable for craftsmen. Wacław’s health was poor during this period, so the company was temporarily supported by Leokadia, the wife of Jan II. Although she had little experience running a business, she had what it takes to achieve success: a strong work ethic, perseverance and attention to detail. An energetic and vital individual, she was strict with both her employees and herself. She assumed the helm fairly quickly and introduced a new order that enabled the workshop, which had been facing collapse, to stand more firmly on its feet.

In 1982 Jan II decided to join the company. Under the watchful eye of his foremen, he learned the secrets of the trade and earned his master certification, which was required in those days. Meanwhile, the rift in the country between the government and the society as represented by “Solidarity” was deepening. The mounting economic crisis exposed the underdevelopment of the socialist economy and led to shortages of every product on the market. Inflation rose several hundred percent, and the only thing that functioned normally in this country plunging headlong into chaos was private small business. The Kielman workshop experienced high turnovers, and skins that couldn’t be obtained through official channels were supplied through the back door by black marketeers. For the first time, customers had to stand in line to place orders with Kielman. So it went until 1989, when political changes brought hope that the company might return to its former glory. The first decision made by Jan and Leokadia was to part ways with the watchmaker who had moved into the workshop thirty years ago.

In the summer of ‘93, the company was joined by a member of the fourth generation – Maciek. The influx of new blood led the company to expand into new areas of activity. Custom-made handbags were added to the company’s catalog. The first serious contacts were made with Viennese suppliers of leathers and wooden shoe trees and with the British clothier Barbour, whose stylish products are showcased today in a separate salon.

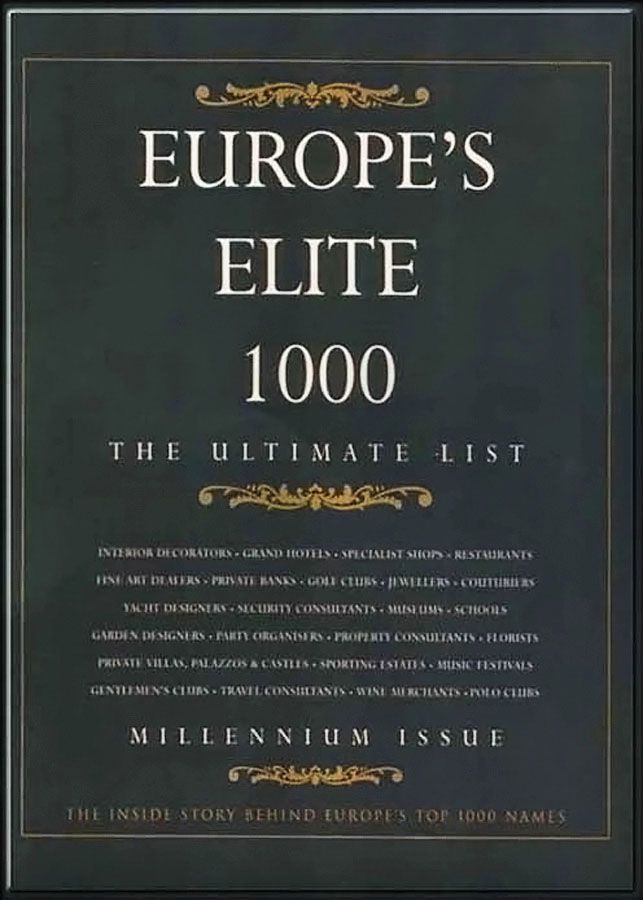

W roku 2000 firma Jan Kielman została zamieszczona w angielskim almanachu „Europe’s Elite 1000, Millennium Issue” mieszczącym opis i krótką historię tysiąca najbardziej ekskluzywnych miejsc w Europie.

A website presenting the company’s activities went online shortly afterwards. The instructions included on the website make it easy for customers to take their own measurements, send them to the workshop and order any style of shoe without traveling to Warsaw.

Since Poland’s accession to the European Union in 2005, the company has consistently had a large quantity of skins that are regularly imported from the best tanneries in the world, including unique, exotic skins procured in accordance with the Washington Convention (CITES).

In June 2008, the company celebrated the 125th year of its existence and the addition of three sons: Jan III, Stefan, Maciek II – contributed by Maciek’s wife Monika. There was a total of 15 full-time employees in this period, along with several apprentices training for a job.

Two years later, the workshop was expanded to include a professional leatherworking department under the rubric of Malton-Kielman that makes wallets, handbags, briefcases and all types of leather goods, including watch bands. Time has shown this to be a decision that perfectly addresses the needs of our customers.

In the past decade, products bearing the “Jan Kielman 1883” logo were delivered to handcraft aficionados in over thirty countries worldwide.

All of the owners of the Kielman company were and still are members of the Leather Craft Guild, a society of Warsaw craftsmen with a tradition that stretches back to the 14th century.

The Kielman family originally lived in the borderland between Germany and the Netherlands. At the beginning of the 19th century, the family settled on Polish soil. Tomas Kielman, the leader of the clan, had been appointed manager of a large estate in Szczepankowo, which fell within the Łomża Governorate. In 1880, one of his sons, the 18-year-old Jan, later known as “the first”, left the family home and traveled to Warsaw to make his fortune.

Once in the capital he began training to work in the confectionary industry, but quickly changed his mind and took a job in one of Warsaw’s many shoemaking workshops. After a three-year apprenticeship he received the title of “master” and went on to open his own workshop on the lively Chmielna Street, house number 3.

Jan was a determined and resourceful young man. Before long, he married Marianna Doley, the daughter of a wealthy family of Warsaw businessmen. He used the dowry he received to expand his workshop, which developed from a modest business into a prosperous firm. As the years went on, the shop facing the street was joined by a workshop and warehouses in the annex, where leather and finished products were stored. It was a good time for entrepreneurs, thanks to the booming economy at the turn of the century and the ready market in Russia. It sometimes happened that nearly half of the year’s production went to contractors in Saint Petersburg.

The First World War did not have a significant impact on the company’s fortune. Despite limits on production and an end to exports to Russia, nothing threatened its position in Warsaw. And despite the urgings of his father-in-law, Jan steadfastly refused to mechanize production, preferring to supervise technical matters personally. For her part, Marianna tended to the finances by ruling the shop with a firm hand. They made a point of spending their free time actively; summers were spent rowing a narrow boat on the Vistula; in the winter they traveled to the mountains.

Their two children were well brought-up and carefully educated. Wacław began studying at the Lvov Polytechnic, while Julia studied philology at the University of Warsaw. Wacław’s studies were cut short by the Polish-Soviet War of 1920. After taking part in the dramatic defense of Lvov, he resolved to travel to Belgium. Later, with a diploma from the Antwerp Business Academy in hand, he obtained an internship at the already famed Bally company in Switzerland. His goal was to enter into a partnership with his father after earning the title of “master shoemaker”. Before long, he was convincing his father to install one of the first neon signs in Warsaw and to place a brass fountain with a floating shoe in the shop window to accentuate the quality of shoes made by Kielman.

In the twenty-year period between the wars, Warsaw abounded in shoemaking workshops that offered world-class services. Among the nearly four hundred shoemaking workshops, the leaders were the legendary Hiszpański workshop, past masters of men’s evening shoes and sports shoes, Leszczyński and Struś Co., which specialized in light women’s slippers, and the small Niedziński workshop, reputed to make the best riding boots.

Kielman was therefore all the more surprised when, in the spring of 1921, he received an order from a French major by the name of Charles De Gaulle, who just before ending his work on a military mission in the town Rembertów outside Warsaw, requested that a pair of officer’s boots be made for him. When this order was fulfilled with particular success, it was decided that officer-style boots and other riding boots would permanently be added to the company’s product catalog.

In 1927, the largest order in the history of the company was received. Female courtiers accompanying Amanullah Khan, King of Afghanistan, on a tour of Europe, ordered a total of two hundred pairs of slippers, claiming that they would never find better ones elsewhere. The ruler procured various goods for his own needs and those of Afghanistan in the countries he visited. From Poland he carried away a contract for locomotives and a substantial number of women’s shoes.

Other prominent customers during this period included: President Ignacy Mościcki, General Władysław Sikorski, Jan Kiepura, Adolf Dymsza, Mieczysława Ćwiklińska, Stefan Wiechecki, Wiech, Marian Brandys and a young Hanka Bielicka, who would later claim never to have worn shoes by any firm but Kielman.

In the 1930s, the shop at Chmielna 1/3 had several display windows, there were sofas and couches to sit on, and at the door stood a Swiss soldier in uniform. Two telephone lines were installed to facilitate communication with customers. Finished shoes were usually delivered to a customer’s house with a penny for “good luck” in the box.

There is no precise numerical data on the number of employees at the beginning of the 20th century, because the company’s documents burned along with the rest of the office during the Warsaw Uprising of 1944. It may be estimated, however, that well over 50 people were employed, and that this number remained constant for a long time. Of course, the most important employees were the masters and the qualified journeymen – shoemakers and craftsmen specializing in shoe uppers. The latter were about thirty in number. Each was capable of sewing between 2 and 3 pairs of shoes each week, which gives an idea of the firm’s capabilities at that time.

The Second World War was of course a very difficult time for businesses and families. Despite the fact that the occupiers allowed business to continue and Germans made up a significant percentage of the clientele, the family was moved from its luxurious apartment on Konopczyńska Street to 34 Mokotowska Street, just below the extraterritorial sixth floor guarded by the emblem of Switzerland. During the uprising that followed shortly thereafter, the shop and the workshop were completely destroyed. But as luck would have it, the contents of the warehouses did not go up in flames, but ended up in the hands of the insurgents. Wacław and his immediate family settled in the Warsaw suburb of Józefów; the rest of the family was scattered – some dying, others emigrating.

The company’s employees met with a similar fate. After the war, Wacław rebuilt the company, but it remained much smaller than its prewar incarnation. Together with his partner Leon Solnicki, he rented a small space at 6 Chmielna Street, a modernist tenement building designed by Henryk Stifelman in 1938, almost right across from the prewar address. Despite its dilapidated ground floor, the building was surrounded by houses that were in relatively good condition. Some tools, skins and lasts had been found in the ashes of the previous location, making it possible for the company to return to some extent to its prewar activities. Former employees returning to Warsaw helped immensely with this.

Unfortunately, it quickly turned out that despite the initial postwar enthusiasm the dismal times of the new system were at hand. Suddenly there were problems with the food supply – unheard of before the war – and it sometimes happened that an order could not be fulfilled unless the customer supplied their own leather. When Wacław Kielman was nominated for vice president of the Warsaw Chamber of Crafts in the 1950s, there were loud objections on the grounds that he could not serve as president for having consistently refused to join the Polish United Workers' Party or any other political party. Unlike other Warsaw shoemaking workshops, the Kielman company – as the last representative of prewar traditions – was barely tolerated by the new authorities. Each time he was summoned for questioning by state officials, Wacław would bring along a sweater and a toothbrush that he had set aside in case he got arrested. During these meetings, they gave him to understand that in the People’s Poland there would be no room for private businesses and it was only a matter of time until the firm would be shut down. To harass him more effectively and keep his company from developing, they decided without consulting him to move another craftsman – a watchmaker from the provinces – into the space that he had renovated at this own expense. Depending on the doctrine in force at a given time or the whims of a state functionary, he was only permitted to employ two or four employees in production. Auditors hunted for even the slightest irregularities in how the books were kept. Nearly every shred of leather had to be described and recorded, and any violation carried the threat of draconian fines. The result of this chicanery, coupled with the risk of tax offsets which ensured that no company had the right to rise, was that Jan II, the grandson of the founder and the son of Wacław, no longer staked his future on the shoemaker’s trade; after graduating from the University of Warsaw, he became a lawyer. At the same time, he developed his lifelong passions: sailing and rowing, mainly as a member of the Warsaw Rowing Society, the oldest sports club in Poland, founded in 1878.

The 1970s saw unexpected improvements that made life more bearable for craftsmen. Wacław’s health was poor during this period, so the company was temporarily supported by Leokadia, the wife of Jan II. Although she had little experience running a business, she had what it takes to achieve success: a strong work ethic, perseverance and attention to detail. An energetic and vital individual, she was strict with both her employees and herself. She assumed the helm fairly quickly and introduced a new order that enabled the workshop, which had been facing collapse, to stand more firmly on its feet.

In 1982 Jan II decided to join the company. Under the watchful eye of his foremen, he learned the secrets of the trade and earned his master certification, which was required in those days. Meanwhile, the rift in the country between the government and the society as represented by “Solidarity” was deepening. The mounting economic crisis exposed the underdevelopment of the socialist economy and led to shortages of every product on the market. Inflation rose several hundred percent, and the only thing that functioned normally in this country plunging headlong into chaos was private small business. The Kielman workshop experienced high turnovers, and skins that couldn’t be obtained through official channels were supplied through the back door by black marketeers. For the first time, customers had to stand in line to place orders with Kielman. So it went until 1989, when political changes brought hope that the company might return to its former glory. The first decision made by Jan and Leokadia was to part ways with the watchmaker who had moved into the workshop thirty years ago.

In the summer of ‘93, the company was joined by a member of the fourth generation – Maciek. The influx of new blood led the company to expand into new areas of activity. Custom-made handbags were added to the company’s catalog. The first serious contacts were made with Viennese suppliers of leathers and wooden shoe trees and with the British clothier Barbour, whose stylish products are showcased today in a separate salon.

W roku 2000 firma Jan Kielman została zamieszczona w angielskim almanachu „Europe’s Elite 1000, Millennium Issue” mieszczącym opis i krótką historię tysiąca najbardziej ekskluzywnych miejsc w Europie.

A website presenting the company’s activities went online shortly afterwards. The instructions included on the website make it easy for customers to take their own measurements, send them to the workshop and order any style of shoe without traveling to Warsaw.

Since Poland’s accession to the European Union in 2005, the company has consistently had a large quantity of skins that are regularly imported from the best tanneries in the world, including unique, exotic skins procured in accordance with the Washington Convention (CITES).

In June 2008, the company celebrated the 125th year of its existence and the addition of three sons: Jan III, Stefan, Maciek II – contributed by Maciek’s wife Monika. There was a total of 15 full-time employees in this period, along with several apprentices training for a job.

Two years later, the workshop was expanded to include a professional leatherworking department under the rubric of Malton-Kielman that makes wallets, handbags, briefcases and all types of leather goods, including watch bands. Time has shown this to be a decision that perfectly addresses the needs of our customers.

In the past decade, products bearing the “Jan Kielman 1883” logo were delivered to handcraft aficionados in over thirty countries worldwide.

All of the owners of the Kielman company were and still are members of the Leather Craft Guild, a society of Warsaw craftsmen with a tradition that stretches back to the 14th century.